Quake victims don't sleep alone

|

|

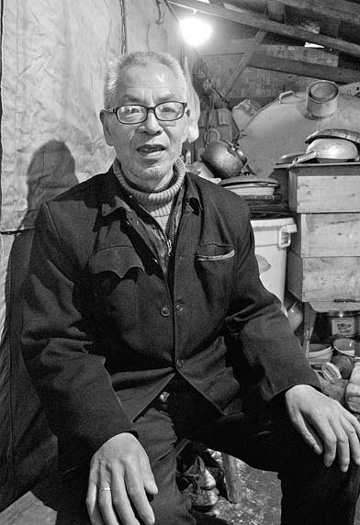

Ma Fuyang, 67, who worked as a cemetery keeper at a mass grave for the May 12 quake victims in Yingxiu town, Sichuan province, sits in his hovel in a mountainside village. |

While most focus on caring for survivors of Wenchuan's earthquake, Ma Fuyang has spent the last three years tending to its dead.

Until last September, the 67-year-old farmer was keeper of the "Grave of the May 12 Wenchuan Earthquake Victims", a half-hectare of hillside cornfield that became a mass grave when soldiers needed to bury about 6,000 bodies - about a third of the population of Wenchuan county's Yingxiu town - to prevent epidemics.

Following the 8.0-magnitude quake, there were too many corpses that had to be buried in too little time to lay the bodies to rest in the traditional way.

So excavators gouged trenches into which the military placed the nameless dead, wrapped in body bags, in groups according to where they were discovered, and covered them with lime and earth.

Among them was Ma's 12-year-old granddaughter, Ma Hongye, one of about 300 students from Yingxiu Primary School who died when the classrooms collapsed.

Because his granddaughter was interred at the grave, Ma volunteered to work there when it opened as a tombstone-filled memorial on June 25, 2008.

During the first year, Ma and Hu Jianguo, 71, who used to work with Ma at the cemetery yard, constantly heard the heartbreaking wails of mourners.

"We would often see primary school students kneeling in front of a mound where it was believed their teacher was buried, weeping and singing the teacher's favorite song," he recalled.

"One man from Fujian province, whose relative was killed at a construction site in Yingxiu, spent three days crying in the graveyard. It made me feel so sad."

But he was made most heartsick by two couples from East China's Zhejiang province, whose children had come to Sichuan after graduation to work at the Yingxiu Power Plant, where they married - and where the earthquake took their lives. The couple returned to the cemetery every Qingming Festival, when the Chinese memorialize their deceased relatives, burn paper money for use in the afterlife and tidy their tombs.

"You could hear them crying before they even reached the graveyard," Ma recalled.

"The mother was so overcome with grief that she flopped on the ground, bawling and clawing at the earth so hard that her fingernails twisted," Ma said.

Ma and Hu tried in vain to comfort the two sets of parents.

"I'd try my best to console relatives. But I'm not a psychiatrist, I'm a villager. All I have are some simple words: 'Don't be so sad'."

That, too, was all he could say to persuade a group of mourners, who had spent the day at the graveyard, to go home when the cemetery was about to close, he recalled.

Ma and Hu received an additional monthly government subsidy of 550 yuan ($83) - besides the monthly 550-yuan subsidy each person from the quake-hit area gets from the government before their resettlement - for their 8 am to 6 pm shifts maintaining the graveyard.

The two retired last September.

"These days, fewer people cry so hard. With the passing of time, it's hard to stay so sad," said Ma, who still lives with his five other family members in a shack built over two tents in a mountainside shantytown, about 10 minutes' walk from the tomb.

The government has built new 90-square-meter houses in town for his family and other households in the quake-hit area.

For the construction of the houses, the government paid the majority of the building cost, which amounts to nearly 50,000 yuan per household. Each family has to pay the rest - about 10,000 yuan - before they can move in.

"We don't have that money yet. So we don't have the key," Ma says, pointing at his new house in the town.

But Ma doesn't complain. With the government's monthly subsidy of 550 yuan per person, the family is now living on 3,300 yuan a month and might be able to save enough money for their new house.

After they move into their new houses, Ma and Hu will not get the monthly subsidy anymore, but they will be entitled to the town's social insurance, which in Ma's case, stands at 660 yuan a month.

Over the past year, Ma said, he still visits the graveyard from time to time, mostly when he is on his way to the town to buy vegetables.

"I don't miss my job. But because I worked there for so long, I have a special attachment to the graveyard," Ma said.

0

0