Bohai oil leaks special: the empty sea

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China Daily, September 5, 2011

E-mail

China Daily, September 5, 2011

Zhao calls it his "12-year war of resistance". During that period, he lost between 100,000 and 200,000 yuan every year. He was only saved from financial ruin by his indoor sea cucumber farm, which brought in about 300,000 yuan a year on the average.

|

|

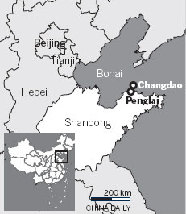

The map of Bohai Bay. [China Daily] |

Many of his peers were not so fortunate and they became bankrupt. Zhao says from more than 1,000 households breeding scallops in Changdao in 1996, now there are less than 100.

At that time, experts and officials said the explanation of the large-scale deaths was the natural genetic biodegradation of seed shellfish. To Zhao, the theory apparently meant that the scallops could no longer adapt to the environment.

But then, after 2008, the situation was mysteriously reversed and the survival rate became normal again. And the farmers were still using the same seed shellfish.

"Did they suddenly stop degrading? It doesn't make sense. It could only be the water problem! Unlike sea cucumbers, scallops are more sensitive to pollution," he says.

It is no secret that the waters of the Bohai has been gradually but inexorably polluted. The water quality is getting worse, and no one knows it better than the Changdao fishermen.

Qu Shunfang, 62, Sister Qu's father, believes the pollution affecting Changdao during those dark years come from paper and chemical factories along the coast of Bohai Bay, a stretch that covers three provinces and one municipality - Shandong, Liaoning, Hebei and Tianjian.

![Qu Shunfang, 62, Sister Qu's father, believes the pollution affecting Changdao during those dark years come from paper and chemical factories along the coast of Bohai Bay. [China Daily] Qu Shunfang, 62, Sister Qu's father, believes the pollution affecting Changdao during those dark years come from paper and chemical factories along the coast of Bohai Bay. [China Daily]](http://images.china.cn/attachement/jpg/site1007/20110905/0014222d98500fcea6c40d.jpg) |

|

Qu Shunfang, 62, Sister Qu's father, believes the pollution affecting Changdao during those dark years come from paper and chemical factories along the coast of Bohai Bay. [China Daily] |

Oil in the seawater is a normal occurrence, long before the latest oil spill. Su Benguo, 56, fishermen, says he does not know where it comes from.

According to him, he used to find asphalt-like black pellets in the stomach of a fish he calls "blackfish", or mullet. Su believes they are solidified oil sediments and fish ate them because they had nothing else to eat. And in spring last year, Su began seeing these black pellets appearing in his nets - sometimes scattered, at times covering the entire bottom.

His son, Su Maodong, 32, is a buyer who purchases seafood from the villagers and re-sells them. He had to trash more than 850 kilograms of red-banded mantis shrimps in 2008 because they were covered with oily black spots.

So how did the situation so suddenly reverse after 2008? What mysterious miracle was at work?

Zhao Fuguo believes it was the result of the government becoming more aware of the pollution problem and its stepped-up measures in controlling the chemical and waste emission and effluence along the coast.

But some things will never be the same. The environmental cost of progress has taken its toll. While the fish-farming is enjoying a second chance at life, the number of natural fish species in Bohai is already seriously decimated.

Qu Shunfang, who switched from fishing to fish-farming about 10 years ago, says there is a lot less fish in the sea now. As he speaks, his eye light up as he fondly remembers all the different fishes he could catch in the 1970s - ribbonfish, mackerel, flounder, yellow croaker and anglerfish.

These were all common, but are now rarely seen or caught. For those still in the business, the reduced catch is a vivid reminder of an alarming situation.

Su Maodong used to harvest several thousand kilograms of jellyfish in one trip. These days, he counts himself lucky if he nets in a few. In the past, with just five fishing boats, he could easily harvest around 2,500 kilograms of red-banded mantis shrimps a day, but now even with 20 ships, he can barely catch 500 kilograms.

Another Changdao fisherman Du Huimin, 64, grew especially nostalgic while talking about prawns. He remembers catching thousands at a time, large ones that weighed 14 to a kilogram. Now he counts it a good day if he even sees one or two.

Du says it's an even luckier day if he sees sharks and whales, creatures that used to frequent Bohai on their migration route. He remembers at least 40 varieties of fish in these waters, but says at least half have disappeared.

Like the other fishermen, he laments the shrinking catch, and tells us he has to cast 20 nets before he can fill a boat while in the past, two nets down and he can head home.

"Bohai Bay is a resting place where fishes come from the south to mate and lay eggs. But when groups and groups of fishes keep dying here, then the fishes will not return," he says.

"Maybe in another 10 years, all the fishes and shrimps will die out."

That is a sad last word from a dejected fisherman, but it should also be a loud clarion call for us to protect our natural resources, and to act now, before it is too late and all the fishing boats in Changdao turn into relics of a better age.