Revival of the space race?

- By Geoffrey Murray

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, September 23, 2011

E-mail

China.org.cn, September 23, 2011

|

|

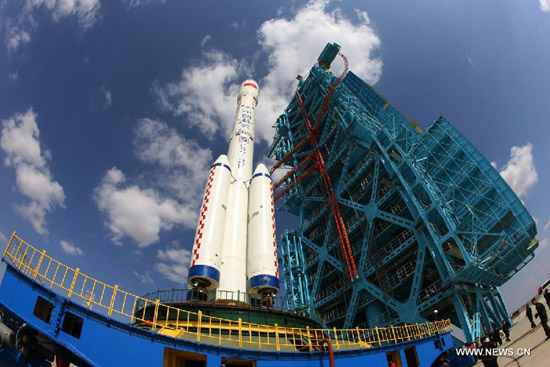

|

A Long March 2F carrier rocket loaded with "Tiangong-1", China's unmanned space module, is moved to the launch pad at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwest China's Gansu Province, Sept. 9, 2011. China will launch its unmanned space module, Tiangong-1, sometime from Sept. 27 to 30, a spokesperson said here Tuesday. [By Qin Xian'an/Xinhua] |

As a boy, I thrilled at the first human ventures into space. Russia's Yuri Gagarin led with a single orbit of the Earth on April 12, 1961, followed by the first American John Glenn who made three orbits on February 20, 1962 (technically, Alan B. Shepherd was first, but he only made a suborbital flight).

With ears glued to a transistor radio, we would listen with growing excitement as the countdown to launch moved towards zero - "T minus 10 and counting" - and that final laconic statement: "We have liftoff."

For a boy growing up on a reading diet of space fiction books and comics, these were heady days, even if the flights must now seem like something from the Stone Age to today's techno-savvy younger generation.

Because of that, I have no problem sharing in the national excitement generated by the steadily mounting achievements of China's space program - never mind that these occurred long after the pioneering American and Russian ventures.

Now, we have the imminent launch of the country's first space lab Tiangong-1 (Heavenly Palace 1), an 8-ton test bed of the technologies China is developing for a space station program. If all goes well, second and third missions will follow. It's possible the second will carry astronauts to live and work on an earth-orbiting vehicle; if not, the third certainly will.

This is a great achievement, and I do not belittle if by seeking to place it in an historical content. After all, this prototype is tiny compared with the 80-ton US Skylab launched in 1973 or the 22-ton module the Russians launched in 1986 to form the nucleus of the Mir Space Station.

Yet, in a sense, China is stepping into a space vacuum. The International Space Station (ISS) has grown to a substantial 450 tons as bits and pieces have been added over the years mainly by the US Space Shuttle program. But the latter has now ended, while the ISS is scheduled for decommissioning in the early 2020s.

This happens to be the time when current Chinese plans called for the launch of a full-fledged space station weighing around 70 tons, effectively becoming the de facto ISS.

So what should we make of all this? Firstly, the space lab is only one part of an ambitious program mirroring in many respects the early American enthusiasm for space exploration.

The last manned U.S. Moon mission took place in December 1972 when the two Apollo 17 astronauts, Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt, made three lunar walks in the Taurus-Littrow valley and left behind a commemorative plaque for some adventurous soul to find someday - perhaps soon.

China, just like the U.S. before it, has been engaged in a graduated program of moon orbits and landings, although the appearance of Chinese astronauts emulating Neil Armstrong's "one small step" is probably still a few years away.

The Americans have turned their gaze further afield in the solar system and beyond, including landings by unmanned vehicles on Mars; in turn, this will be matched by Chinese missions to both Mars and Venus.

Inevitably, there are those in the West who find something sinister in all this activity, such as the idea that it is part of China's bid to become a world strategic power, gaining global hegemony by its control of near space.

There is a strong sense of déjà vu here. America's crash program for landing men on the Moon was triggered in part by Russian success in getting into space first; with the Cold War raging, there were fears that military confrontation would not be restricted to our humble planet.

The two countries finally saw sense, however, accepting that putting a few men (or women) into space provided no military advantage whatsoever. From that grew the close cooperation between them that helped develop the ISS.

There are some who see no reason why China and the U.S. cannot do the same, but, unfortunately, Washington currently bans NASA from such cooperation apparently fearing loss of technological secrets.

What does make Americans somewhat nervous is the technological skill now being tested through the space program could spillover into the military field. But, after all, didn't many of the American scientific advances that helped propel the Apollo Moon program and others also ended being incorporated into military hardware? So, why should China be any different?

However, we might be looking in the wrong direction. There are a number of Western analysts who feel the real significance of Tiangong-1 is that it shows China moving ahead of India and Japan in the race to be Asia's number one space power.

Depending on the economic situation, both might feel impelled to drastically bolster their space programs - although, as the U.S. and Russia have found, a space race imposes very high financial penalties.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/geoffreymurray.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.