Redevelopment akin to rewriting history

- By Geoffrey Murray

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, January 9, 2012

E-mail

China.org.cn, January 9, 2012

The announcement on Dec. 29 by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH) that around 44,000 of China's 766,722 registered heritage sites had disappeared reflects the complex challenge of balancing economic development with cultural preservation.

|

|

|

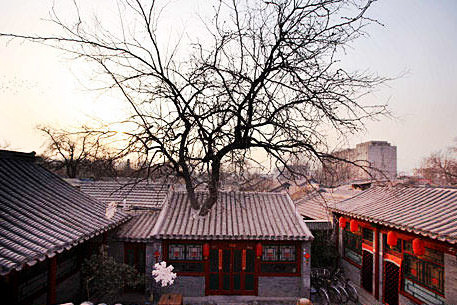

Beijing Siheyuan represents the capital's architectural style. [File photo] |

Of course, China is not alone in this; there are many places where developers' bulldozers, desire for tourist dollars, ill-informed neglect and environmental change are destroying vital links with the past. According to the Global Heritage Network website the "archaeological record of human civilization - our global heritage - is vanishing [representing] a permanent loss to the planet, akin to endangered species loss".

SACH Director Shan Jixiang told a Beijing press conference that apart from total disappearances, around 17.7 percent of cultural relic sites were relatively poorly preserved and 8.43 percent in a state of disrepair. The main reason is demolition in the name of economic construction; most sites had only local, rather than national legal protection making them vulnerable when a local government decided to "modernize".

During long residence in China, I've seen this time and again. One of the delights of Beijing when I arrived in 1990 was to find new routes between office and home by cycling down narrow hutongs (alleyways) lined with siheyuan (homes in quadrangles hidden behind high walls) typical of the old city. At the start of the 1990s, there were still 1,320 hutongs but now fewer than 400, as they make way for wide highways lined with modern office buildings and high-rise apartments.

|

|

|

New Skyscrapers in CBD, Beijing. [File photo] |

And, to me, one of the biggest mistakes made by the PRC in the 1950s was to demolish the distinctive city walls in order to improve traffic flow. If you want to see what impact they can make as a tourist attraction go to Xi'an, the ancient imperial capital that treasures its old ramparts.

The SACH report says around a quarter of Beijing's heritage sites have disappeared. It recalls a very apposite remark someone made a few years ago in lamenting such destruction: Beijing could be transformed into New York in 50 years, but New York could not be transformed into Beijing in 500 years.

Disregarding all the Chinese signs around the city many foreign visitors could be forgiven for thinking they had never left home.

Another example is Sanfang-Qixiang (literally three lanes and seven alleyways), the most representative historical site in Fuzhou in southern Fujian Province with a history dating back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

Situated in the heart of downtown Fuzhou, the area was a mix of small residences with tiled roofs and walls, and sprawling residences of rich and famous people many dating back to the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The latter homes featured exquisite wood carvings on the windows and doors and lush green gardens of great tranquility.

The area also nurtured many folk arts such as Min opera, professional storytelling in the local dialect, stone carving, silk umbrella making and special local lacquer ware.

However, the local government, noticing the tourist potential, made grandiose plans to redevelop; the project has been underway for three years with mixed results. The principal axis is Nan Hou, where a succession of coffee bars, clothing stores and other Western-style shops have obliterated part of its traditional Chinese character. Many folk artists have been driven out and there's no longer a place for performing Min Opera.

Then there is the old town of Lijiang, in southwestern Yunnan Province, typified by idyllic scenery where narrow alleys and rippling streams thread their way among the unique architecture of the Naxi, a small ethnic minority group. In 1997, UNESCO placed old Lijiang on its World Heritage List, but a recent inspection mission attacked over-commercialization and loss of traditional community values

The reason is obvious: Lijiang is on the world tourist map and now receives six million visitors a year, far more than it can handle and stay true to itself. Hordes of tourists bring hotels, bars and coffee shops that scar the landscape with their ugliness.

There is always a dilemma for local governments in balancing the relationship between protection and conservation of historical sites and the desire to generate local revenue through tourism.

But, if there's nothing special to see, the tourists will stay away. Look at Singapore: in the 1980s, when I lived there, the government decided to demolish some traditional Chinese areas deemed to have become slums. Chinatown was renovated but proved disappointing to tourists as too sanitized and artificial. Bugis Street, a colorful but seedy Vietnam War-era haunt of transvestites, was bulldozed, only to reappear as a boring modern suburban shopping mall.

The artificial recreation of ancient architecture and traditional culture can never be a substitute for the real thing. The more we destroy, the more we lose touch with our roots - and that's sad.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit: http://m.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/geoffreymurray.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.