FDI slowdown will spur industrial transformation

- By Geoffrey Murray

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, April 3, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, April 3, 2012

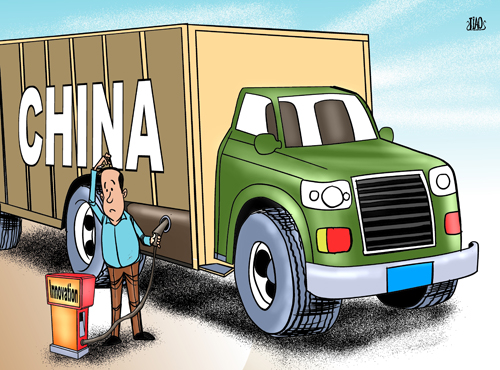

China's recent slowdown in foreign direct investment (FDI) combined with its reduced economic growth targets raises questions as to whether the "China boom" is running out of steam.

|

|

|

Running out of gas[By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

Despite such caricatures, this phenomenon marks an inevitable watershed in China's economic development - from quantity to quality and from basic manufacturing to growth into other areas like services.

The ability of other countries to invest in the world's second largest economy inevitably is linked to their own economic health, and events like the European debt crisis have not helped in that regard. In addition, virtually all the world's leading manufacturers have poured vast amounts of capital into China and a cooling off period is surely inevitable on both sides.

Sharply rising wage costs in China will definitely lead to some enterprises shifting operations to other developing countries in Asia and elsewhere. The recent furor over alleged poor working conditions and low pay at Foxconn's factories in Guangdong producing Apple's iconic computer and cell phone products (as well as assembly lines working on behalf of other big names such Intel, Microsoft, Nokia and Sony) shows how sensitive this issue has become.

Based on the available evidence, I don't see China losing its image as the "world's workshop" in the foreseeable future. But workers' demand for higher pay, combined with the government's desire to promote economic equality to ensure social stability, will certainly impact some sectors.

Until now, China has benefitted because it is big in every respect: big market, big workforce, big economy, and big ambitions to become a major world power.

Foxconn perfectly illustrates this aspect. It is spending US$1.1 billion to double the capacity of its Zhengzhou factory to produce 400,000 iPhones. The Zhengzhou factory, incidentally, employs 130,000 people. By any criteria, these are mind-numbing figures.

Of late, however, there has been a lot of discussion as to whether this emphasis on grand scale is always the most appropriate business strategy. The answer, for some analysts, is no.

When China first began seeking foreign investment in the 1980s, a lot of low-tech enterprises, such as Japanese textile manufacturers, moved in to take advantage of the extremely low-cost labor and lax environmental regulations. As costs rose and the Chinese government sought to move manufacturing up the ladder to more capital and technology-intensive processes, many foreign-owned manufacturing operations started moving out to places like Vietnam, Cambodia, and Bangladesh.

Recent studies suggest such countries have a lot of advantages when it's not merely a question of mammoth production scale (ala iPhone). There is a clear trend among big retailers in Europe and North America to seek customers by offering a wider range of products that will differentiate them from the opposition.

In this regard, it can be argued, a country like Vietnam is better placed to win new manufacturing contracts by offering flexibility in meeting smaller orders for a wider range of products with frequent changes that require rapid retooling.

I recently read an interesting report on a Swiss-owned pottery export business in southern Vietnam that works with 40 family-based businesses producing a vast range of products cheaply and quickly. It quoted the analysis of Bangkok-based Tractus, which advises manufacturers looking for the right place to invest in Asia, that this typified a shift in global manufacturing from a focus on large scale, low-wage production to a more dynamic approach.

Some companies, it said, would continue to chase a cheap labor supply, looking for countries with a young population. Others, it argued, will chase talent; some, lower tariffs; and some, big markets like China, India and Russia.

Of course, China has many advantages, such as its vast scale, superior infrastructure and supporting industries. However, other countries in the region are catching up, and that means China will need some strategic rethinking on how to stay ahead in the FDI race.

A study published in February by the UK-based Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) concurred that hikes in inflation-adjusted wages, which have averaged 12 percent in the past few years, would inevitably limit the amount of FDI headed toward the mainland.

Soaring costs in China's more affluent coastal provinces, the study said, will hurt investment in coastal manufacturing operations and cause capital to instead shift towards China's lesser developed interior provinces.

Chongqing, in China's southwest, was ranked a lowly 22nd among 31 provinces and municipalities in attracting FDI as recently as 2007; now, it's among the leaders. Sichuan Province (to which Chongqing previously belonged before becoming a municipality under the central government), is likely to attract US$18 billion in new investment by 2015, although this is dwarfed by the US$50 billion flowing into the northeast rustbelt province of Liaoning, the EIU predicts.

Meanwhile, following a Western trend (e.g. Britain), China's rich coastal provinces will gradually move out of manufacturing into services.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit: http://m.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/geoffreymurray.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.