The pursuit of happiness – Chinese style

- By Stuart Wiggin

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 19, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, October 19, 2012

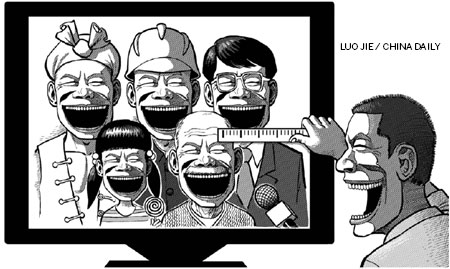

A recent CCTV program asked a myriad of people from across China whether or not they felt happy in today's society. In doing so, the show sparked much debate within China's social networking sphere as the rest of the population weighed in their two cents on the topic. Some microbloggers poured scorn upon the television program, criticising its journalism style and noted that happiness is a subjective feeling which cannot be realistically assessed by respondents in front of a television camera. However, the program has spurred many people, including myself, to address a more specific and very interesting, question: Are people in China happy and can this happiness ever be quantified?

In April of 2012, the first world happiness report was issued by the Earth Institute, commissioned by the UN for its Conference on Happiness. The results were as expected; the world's happiest people all reside in Northern Europe, where the level of social benefits is high. China, meanwhile, failed to make the top 100. The survey took into account education, housing, health, jobs, community, work-life balance, income, as well as environmental factors. These are all topics that are regularly debated within the country's press and the rapidly modernizing economy has put the spotlight firmly on the issues of income, jobs and housing. Add to this factor that of the ageing population and the possibility of raising the age of retirement, the issues become even more prominent, especially when we take into account that the majority of the nation's ageing population does not possess the necessary skills to be able to compete in China's modernizing economy.

It is more than likely that the overtly public aspect of the questionnaire carried out by the CCTV show caused results to be skewed. After all, who would want to let the nation know that the overall population is unhappy at a time when China is more affluent than ever before. Furthermore, despite the intention of wanting to improve the overall image of Chinese society, these types of activities largely tend to ignore the gaping holes that still exist within it, especially with regards to the millions that still live below the poverty line.

And yet, separate studies carried out within China, by the Financial and Economic Affairs Committee of the National People's Congress and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences respectively, suggest that the majority of urban Chinese are relatively happy in today's modern society. In contrast to these Chinese surveys, a group of researchers led by Richard A. Easterlin, university professor and professor of economics at the University of Southern California, published a report last April entitled "China's life satisfaction, 1990 - 2010" in which he disclosed some interesting findings.

Easterlin and his colleagues asserted that the urban Chinese citizens, when asked about their contentment with life as a whole, are less satisfied now than they were a decade ago. Some of the reasons cited for the lack of life-satisfaction included the loss of an extensive employer safety net, subsidised food, health care, housing, and pensions as the economy transitioned into its present market capitalist form. Taking into account the difficult financial situation for the majority of the population, alongside constant news bits regarding food safety concerns and increased international tensions, it's easy to see the amount of strain that Chinese citizens may fall victim to.

Easterlin et al. noted that: "One may reasonably ask how it is possible for life satisfaction not to improve in the face of such a marked advance in per capita GDP from a very low initial level. In answer, it is pertinent to note the growing evidence of the importance of relative income comparisons and rising material aspirations in China, which tend to negate the effect of rising income." And alongside rising expectations, we should also remember that China possesses an enormous number of millionaires, whom millions of youngsters across the country hope to imitate and emulate. However, in order to truly understand the issue of happiness within China, we must delve a little deeper.

China Radio International's Natalie Thomas recently produced a video series entitled "Young Chinese Dreams" in which she talks to three young Chinese people with incredibly different life circumstances. One of the series' subjects, Zhang Guanghui, is a street dancer whose mother and father passed away when he was in his late teens. Despite his struggle to earn a living by doing the one thing he loves the most, Zhang displays incredible optimism. So too does Ren Xiaoning, a young girl who moved to Beijing soon after graduating, only to discover that the competitive elements of life and the cost of living in the city prevent her from achieving her dreams.

The series goes on to introduce Zhao Yun, a privileged girl who has been educated in Italy and currently works in the fashion industry. Her concept of life is far removed from that of the series' other two subjects, and her happiness is all but guaranteed by the fortunate circumstances she was born into. Asking these three individuals whether they are happy is akin to asking three separate questions, as each one has inherited a certain set of values from the social class they were born into. For this reason, to ask someone the general question "Are you happy?" is doomed to receive an inclusive response from the outset. The more reasonable question to ask would be that of "What aren't you happy with?" - though this might not have provoked the image-building scenes that CCTV was probably hoping to achieve.

The author was educated at Oxford University and is a columnist for China Radio International.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.