Long-term policy reflects responsible leadership

- By Dan Steinbock

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, February 23, 2016

E-mail China Daily, February 23, 2016

|

|

|

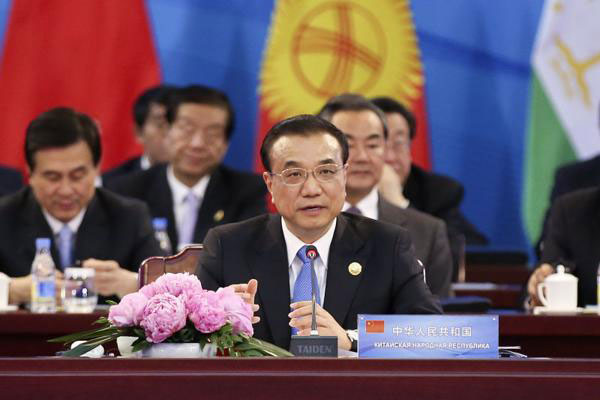

Premier Li Keqiang speaks at the 14th Meeting of Prime Ministers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization addresses the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), saying it should focus on building six cooperation platforms, in Zhengzhou, Henan province, on Dec 15. The platforms will cover six fields: security, production capacity, interconnectivity, innovative finance, regional trade and peoples' livelihoods. [Photo/Xinhua] |

Since spring 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping has stressed that China must adapt to an economic new normal. In the short-term, that means slower growth, painful restructuring and conflicting responses following fiscal accommodation.

At the 2015 Central Economic Work Conference, the policy authorities pledged to focus increasingly on supply-side reforms, which prioritized the reduction of excess capacity while maintaining stability. That is likely to mean expanded fiscal spending and further monetary easing. As an effort to stimulate economic growth, the supply-side reforms represent the other side of the new normal.

In the foreseeable future, China will emulate neither the laissez-faire doctrines of the United States, which led to the global crisis, nor Europe's social accommodation, which is no longer supported by the region's growth.

In contrast, supply-side reforms seek to facilitate China's transition to a post-industrial society.

A hard landing describes a business cycle in which an economy slows down sharply or tips into recession after a rapid growth performance due to government efforts to rein in inflation. A hard landing can also be the unintended result of a central bank's efforts to tighten monetary policy to slow down growth and contain inflation.

Since the global financial crisis, many observers have argued that China is in the midst of such a hard landing. I have argued that they are wrong.

First, a hard landing is predicated on a central bank being willing to hike up rates to slow growth. In reality, the People's Bank of China has been cutting interest rates since early 2012.

Second, a hard landing indicates rising inflation. And yet, since late 2011 when inflation peaked at more than 6 percent, inflation in China has gradually decreased to less than 2 percent.