Xi Jinping's new book: An essential primer for understanding China

- By John Ross

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, February 24, 2018

E-mail China.org.cn, February 24, 2018

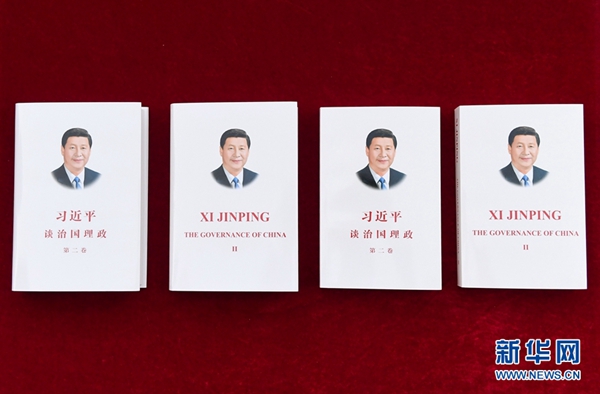

Second volume of Xi Jinping's The Governance of China [Photo/Xinhua]

For anyone aiming to seriously study China's present and future policies, the second volume of Xi Jinping's The Governance of China, together with its companion earlier volume, is by far the best place to start.

The reason is clear: why read those who are merely interpreting what is happening when it's possible to directly read the analyses of the key person determining the decisions?

China's Foreign Languages Press, therefore, is making a big contribution to international understanding of China by publishing this volume in a timely manner – it brings together Xi Jinping's speeches up to September 2017.

This removes any excuse for non-Chinese writers to spend time merely reading foreign assessments of China without studying the country's own analysis. Chinese people would be astonished to know how many Western so-called "China experts" have never read any works of Deng Xiaoping or Mao Zedong, but, instead, only Western biographies or commentaries on them!

The fact that over 1,000 pages of Xi Jinping's speeches are now collected in English, and these have been widely bought and promoted internationally, means readers have ample opportunity to read the Chinese president's analyses, and anyone who has not done so evidently cannot be considered well informed on China.

As the latest volume covers 600 pages, it would be impossible to make a comprehensive review in the short space available here. The 17 sections range from rule of law, through culture, to the environment. Rather than skip over numerous topics in a superficial way it is better to concentrate on one, which may be taken as typical of the significance of the whole, and analyze its links to other sections of the book and to the previous volume of The Governance of China. As for those outside China, the country's primary impact will be through international relations and foreign policy, so this issue will be chosen for discussion.

A shared future for humanity

Xi Jinping's concept of a "shared future for humanity" outlined in this volume has always been the most intellectually-coherent analysis of global affairs – as will be shown. The new development, particularly since Xi's speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017 (contained in this volume), is that the big impact of its analysis is now admitted internationally even by those strongly in disagreement with China.

Steve Bannon, former chief strategist to President Trump, a clear opponent of China, stated starkly: "I think it'd be good if people compare Xi's speech at Davos and President Trump's speech in his inaugural."

Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, recently noted: "An important factor in persuading Mr Trump to attend the WEF was that the star of last year's Davos was China's President Xi Jinping. Mr Xi took the opportunity to position China as the champion of free trade, telling a delighted audience that 'pursuing protectionism is like locking yourself in a dark room'.'

U.S. National Security Adviser H. R. McMaster, and Director of the U.S. National Economic Council Gary Cohn, meanwhile, jointly authored a Wall Street Journal article de facto attempting to set out an alternative to Xi Jinping's analysis.

Globalization

President Xi's endorsement of the fundamentals of globalization is unambiguous: "Economic globalization is a result of growing social productivity, and a natural outcome of scientific and technological progress." In consequence, "Economic globalization… has greatly facilitated trade, investment, flow of people, and technological advances.

"Since the turn of the century… 1.1 billion people have been lifted out of poverty, 1.9 billion people now have access to safe drinking water, 3.5 billion people have gained access to the internet, and the goal has been set to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030. All this demonstrates that globalization is generally good.

'Of course, there are still problems, such as development disparity, governance dilemma, digital divide, and an equity deficit. But they are growing pains. We should face these problems squarely and tackle them. As we Chinese like to say: 'One should not stop eating for fear of choking'."

Economic roots of globalization

Such clear support of globalization in foreign policy is directly rooted in fundamental economic analysis. The first sentence of the founding work of modern economics, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, declares: "The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labor… have been the effect of the division of labor."

The decisive advantage of such a division is that, by producers interacting in their productive activities, the resulting output and productivity is much greater than the sum of their individual efforts – as President Xi states it in popular fashion, in economics: "one plus one can be greater than two."

This economic reality destroys the concept that international relations are a "zero sum game." Instead of a "zero-sum" situation, both or indeed many sides, by engaging in division of labor, can all gain.

This, naturally, does not mean that there are no longer any conflicts between countries. However, it means they have a more fundamental common interest in that the prosperity of each state depends on an international division of labor – that is, the prosperity of each country depends on the activities of other countries. This creates the reality of an international community – a "common future for humanity."

China's foreign policy concept of "win-win" outcomes, as outlined in this volume, is therefore not warm words, but reflects this fundamental economic fact.

This economic reality, therefore, also provides an even firmer foundation for dealing with the common problems humanity faces, and therefore affecting its "shared future," than the fact that, as Xi Jinping put it in a recent speech to the dialogue of foreign political parties with the CPC, that all humanity necessarily has to share the same planet.

Certainly, numerous issues ranging from terrorism to climate change can only be tackled at an international level. Regarding the latter, for example, President Xi notes: "We should make our world clean and beautiful by pursuing green and low carbon development. Humanity must coexist with nature, which means any harm to nature will eventually come back to haunt humanity."

However, the international division of labor also means that the prosperity of each country is tied up with the development of other countries. This means different parts of the world are linked and therefore benefit or lose together – creating in a most direct economic sense a common destiny of humanity.

Diversity

This, however, immediately poses another question. A division of labor produces benefits not because those participating in it are the same, but because they are different. If they were the same, there would not be the same benefit. The division of labor in the modern world is necessarily international in scope – the age when even the largest national economies could be essentially self-contained is long past. As President Xi puts it: "In today's world, all countries are interdependent and share a common future."

This, therefore, creates a further pillar of Xi's concept of "a community of a shared future for humanity." Diversity is not a disadvantage, something to be feared, but it contributes to human development. As Xi puts it, citing China's classic History of the Three Kingdoms: "Delicious soup is made by combining different ingredients."

Diversity in human civilization not only defines our world, but also drives human progress. Civilizations are different, and only in identity and location. Diversity in civilizations should not be a source of global conflict; rather it should be a driver for progress.

Diverse civilizations should draw on each other to achieve common progress. Exchanges among them should become a source of inspiration for advancing human society and a bond that keeps the world in peace.

Instead of an attempt to impose uniformity, a single model considered "superior" to all others, and involving attempts to impose it on others, China's foreign policy precisely embraces the diversity of different countries.

President Xi directly draws conclusions from these fundamental concepts: "We should […] build a new model of international relations featuring mutually-beneficial cooperation, and create a community of a shared future for humanity. To achieve this goal, we need to make progress in the following areas:

"We should build partnerships in which countries treat each other as equals, engage in extensive consultation, and enhance mutual understanding. The principle of sovereign equality underpins theCharter of the United Nations. The future of the world must be shaped by all countries.

"All countries are equal. The large, the strong, and the rich, should not abuse the small, the weak and the poor. The principle of sovereignty is not just embodied in the inviolability of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries. It is also embodied in the right of all countries to make their own choice of social system and development path."

In short, the fundamental and interrelated concepts in Xi Jinping's analysis are the mutual advantages of an international division of labor on which modern prosperity is based, therefore indeed providing a shared destiny of humanity, recognition of diversity, and equality of countries.

The alternative

To understand the profundity of Xi Jinping analysis, it is worth contrasting it with the main alternative being promoted internationally. In what was really an attempt to reply to Xi Jinping's Davos speech, U.S. National Security Adviser McMaster and Director of the National Economic Council Cohn jointly authored a Wall Street Journal article, which could not have appeared without sanction from the highest authority in the land.

In this they proclaimed: "The world is not a 'global community' but an arena where nations, non-governmental actors and businesses engage and compete for advantage." Or, as they put it drawing the practical conclusion: "America First signals the restoration of American leadership." This, therefore, is a profoundly unequal concept of international relations – in its most grotesque form expressed in vulgar references to "s**thole countries."

Xi Jinping's concepts on foreign policy in this book are the most advanced of any major political leader in the world. There is, bluntly, no work by a Western leader that is its equal. Because it is an integrated concept, ranging from economic foundations to direct conclusions on relations between countries, it is capable of providing a firm long-term basis for China's foreign policy in a way that corresponds to the interests of other countries.

China's foreign policy, therefore, does not consist of a series of unconnected initiatives but has a coherent underlying approach and strategy as set out in this volume.

It is worth buying the book just to read the section on foreign policy. However, as already noted, there are numerous other sections each of which provides the best starting point for understanding China's policy.

John Ross, Senior Fellow, Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China, is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/johnross.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.