Philosophy

The development and features of Chinese philosophy

"Misfortunes of a nation may turn out to be fortunes of a philosopher," noted Qian Mu, a renowned expert in Chinese cultural studies.

The sentence vividly summarizes ancient Chinese philosophers and their work, with Chinese history providing verification through the passage of time. In the majestic periods of Chinese history like the Han (206BC-220AD) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, major achievements in the humanities occurred in the field of literature, but at times of social unrest, philosophical accomplishments were even more prominent.

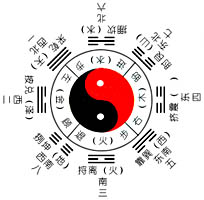

Ancient Chinese philosophers were born out of sorcery. After a series of incidents, ancient belief systems in destiny were gradually shaken and finally collapsed. The symbolic events that indicated the birth of Chinese philosophy were all developed by historiographers and senior officials in the government of the Zhou Dynasty (about 11th Century-221BC) helping to explain natural and social phenomena. The old-type sorcerers, who were most used to providing theological explanations, discarded their most familiar habits of resorting to augury, and emerged anew as philosophers, trying to give logical explanations by employing reason. Chinese philosophy, as a new form of culture, was born.

Features

However, because of their unique identity as sorcerers, Chinese philosophers were not merely pursuing knowledge out of a pure "love of wisdom" as did their western counterparts. While they also tried their best to explain naturally occurring phenomena, what concerned them most were social issues. The purpose of learning the "orders of things" was to provide a better and more complete systematic explanation to human matters, rather than solving the problem of the absence of spiritual dependence after the collapse of primitive religious beliefs in ancient China.

The specific social and historical conditions that nurtured the birth of Chinese philosophers have not only contributed to the features of Chinese philosophy, but also influenced the characters of Chinese people. "To examine heavenly order to learn human affairs," -- perhaps considered the prime task by ancient Chinese philosophers -- characterized Chinese philosophy with the distinct feature of giving great attention to societal needs. The focal point on people led to Chinese philosophers' suffering and worries about society, especially at the times of social chaos.

On the other hand, ancient Chinese had a good tradition of theoretical thinking. Though the focus was always on human affairs, Chinese philosophers were always looking for a reason to develop thought that explained ordinary or mundane affairs of the day-to-day world.

These characteristics of Chinese philosophy and various philosophers contributed greatly to the historical development of the nation, with some believing that the "misfortunes of a nation may turn out to be the fortune of its philosophers."

Development stages

Before the Qin Dynasty (221-207BC), traditional values from the Zhou Dynasty gradually collapsed, with different regimes and different thoughts flourishing throughout China. According to official records of the Han Dynasty, there are as many as 189 different schools of thoughts at the time, making that period the pinnacle of Chinese philosophy. Scholars in the Han Dynasty summed up the pre-Qin philosophy in "nine genres and 10 schools."

At the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), the notion that "heaven is dead" prevailed; Confucian moral concepts and values waned; and, society experienced major turbulence. Philosophers at the time used r metaphysical discussions on the interrelation between Confucianism and Taoism to explain a number of important topics like the relationship between Confucianism and nature. Theoretical hypotheses were unprecedented during this time.

From the Tang to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), traditional values suffered from disorder as the Han people blended with other ethnic groups. The contradictions between foreign and indigenous cultures, and official and folk cultures, were more glaring than ever. Facing the contradictions, Han Yu and Li Ao made their voices heard, followed by the "three doctors at the Beginning of Song Dynasty," Sun Fu, Shi Jie, and Hu Yuan, as well as "five scholars in the Northern Song Dynasty," Zhou Dunyi, Shao Yong, Zhang Zai, Cheng Hao, and Cheng Yi. The Confucian school of idealist philosophers endeavored to re-establish a spiritual world for the people in the Song Dynasty, with their efforts to integrate Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism.

At the juncture of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1644), a generation of scholars chose secluded lives in the mountains and temples after the Manchu Ethnic Group seized power. They sorted out a traditional system and rules, and profoundly criticized and meditated on traditional culture. A galaxy of philosophers with noticeable achievements like Wang Fuzhi, Gu Yanwu, Huang Zongxi, and Fang Yizhi brought Chinese philosophy to a profound new theoretical height.

In modern times, the "Middle Kingdom" was repeatedly defeated by the imperial countries, and the nation's confidence was at its lowest point ever. The task of the time was to "save the nation from subjugation and ensure its survival." Chinese philosophers researched a wide range of subjects on ancient, modern, eastern, and western philosophies, striving to improve China's own philosophy. The trend is still continuing today, forming a new mixed cultural philosophy.

As a result of its features, Chinese philosophy has always had a close relationship with society in its development process. The "misfortunes" the nation has suffered from time to time presented major philosophical challenges, and the "fortunes" of philosophers were vital creations as responses to philosophical subjects of the time.

Whenever Chinese philosophy experienced a thriving period, a number of different schools, abundant talented people, the extent of freedoms, and scope of studies tended to surpass the previous period. The rise and decline of Chinese philosophy has much to do with the rise and decline of society, shaping characteristics and connotations of the nation's ethos. (chinaculture.org)

0

0