Confronting criticisms in Sino-African ties

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, May 18, 2012

E-mail China Daily, May 18, 2012

Africa is a zero-sum opportunity and China is squeezing others out

Challenge: China dominates the continent and is squeezing traditional partners out.

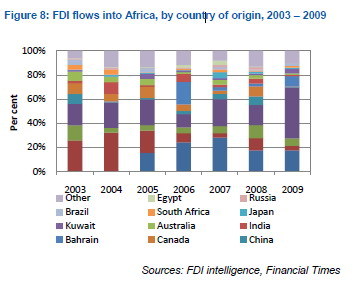

Chinese influence has grown swiftly across Africa. In conjunction with China's expanding commercial engagements, China has made major political advancements on the back of high-level visits. Trade between China and Africa has grown significantly faster than with any of Africa's other partners. Interestingly, the speed at which Chinese engagement has accelerated over the past few years has occurred at a time when interest from more traditional development partners has stagnated. Europe's share of Africa's trade has halved since 2000. Nevertheless, both the US and European Union (EU) have strong positions in Africa. Furthermore, in Lusophone Africa, Brazil is offering stiff competition to Chinese expansion. In fact, President Lula was a guest of honour at the African Union summit in Sirte, Libya, in July 2009. In East Africa, a large diaspora network offers India an important foothold in Africa, presenting unique opportunities for corporate expansion.6

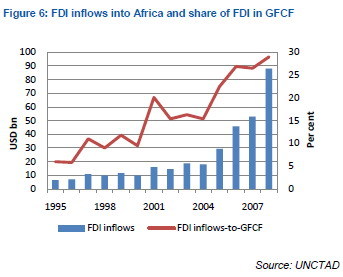

Promisingly, as both a cause and consequence of Africa's internal reforms and more attractive economic growth trajectory, inward FDI into Africa increased five-fold from USD14 bn in 2002 to USD87.6 bn in 2008. (UNCTAD?s Global Investment trends monitor expects FDI inflows to have fallen in 2009 to USD56 bn.) And FDI has played a growing role in value of additions to fixed assets purchased by business, government and households. Consider that the share of FDI inflows in Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in Africa has increased steadily from below 10% in 1995 to a peak of near 30% in 2008.

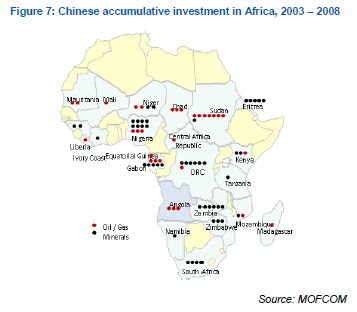

China's accumulative FDI stock has been critical for Africa's economic growth and development. China's FDI into Africa neatly aligns with the long-term strategic perspective China presents towards the continent. "The growth of Chinese FDI reflects a Chinese decision at a high level to contribute to South-South cooperation through mutually beneficial commercial relationships with the African continent" (Besada et al., 2008:7). Despite a great deal of media attention, China FDI inflows have grown, from USD520 mn in 2006 (Besada et al., 2008) to USD1 bn in 2009. Therefore, quite astonishingly, China accounted for less than 2% of the total FDI inflows into Africa.

In terms of FDI stock, Europe and the US account for 36.6% and 37%, respectively, of total FDI into Africa. Furthermore, in terms of FDI flows, flows from China are dwarfed by inflows from advanced economies. Moreover, China is facing increasingly stiff competition from other emerging markets, such as Brazil, India, the United Arab Emirates, Malaysia, Turkey and others.

Even in Africa's hotly debated energy sector, which has attracted the most Chinese interest, Sonatrach7 alone produces almost ten-times more crude oil per day than the combined output of China's National Petroleum Company, Sinopec and Sinochem. Evidently, the legacy of Africa's more mature bilateral arrangements remains an important advantage. Mainstream partners are currently dominant and advantaged owing to their historical hegemony in the continent. And, in Nigeria's energy market, China plays second fiddle not only to energy majors from the mature world, but also to Indian and Brazilian energy firms.

China is now a formidable player in the topography of influence on the continent. Moreover, the clear political will to magnify the relations implies China?s engagement has just started. Consider the targets outlined at the FOCAC in 2009, which have captured the imagination: China has penned an investment targeted of USD10 bn per annum and USD10 bn in bilateral support by 2012. Therefore, China will be Africa's second-largest donor nation, largest trade partner and a dominant continent-wide investor.

China is supporting Africa's much-needed, growth-inspiring and productivity-enhancing infrastructure re-build. Africa needs to expand economic activity by a tempo of around 8% each year for the next few years to have any reasonable chance of meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). Short fleeting spurts of economic growth have proven unable to catapult countries into a modernised international economy. In recent years, an overwhelming consensus has emerged that unwaveringly recognises that Africa's physical infrastructure deficit is an urgent and serious impediment to the continent's development alchemy and economic genesis. Between 1960 and 2005, increases in Africa's infrastructure stock contributed one percentage point (pp) to per capita economic growth each year, while the aforementioned structural improvements contributed 68 basis points (Calderón, 2008) (see Figure 10).

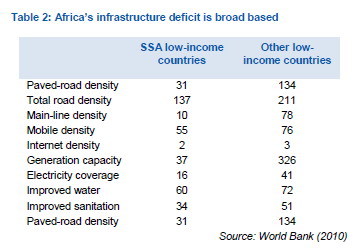

The difference between capital stock per capita between developed and developing economies is typical. For instance, Switzerland's capital stock is 53 and 93 times larger than China and India's, respectively. However, Africa's capital stock is a mere fraction of these emerging economic giants. For instance, paved-road density in low-income African countries stands at 34 kilometres (km) per 100 square km of arable land, as opposed to 134 for other low-income countries. In fact, across a whole host of measures, Africa is a noticeable laggard. Worryingly, African deficiency in power infrastructure has impinged economic activity most pervasively. Interestingly, Africa had almost three times more electricity-generating capacity per million people than South Asia in 1970, but by 2000 South Asia had twice Africa's generating capacity.

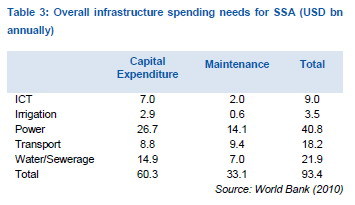

In 2005, Africa's infrastructure need was estimated to be USD39 bn each year. Other estimates suggest that investment in African infrastructure needs to be at five per cent of GDP per year, plus an additional four per cent for operation and maintenance. Currently, total expenditure on additional investment in infrastructure averages around 2.5% of GDP. The World Bank now estimates that USD93 bn is actually required annually to upgrade Africa?s infrastructure to the level of developed economies.

The World Bank concludes that Africa must develop an additional 7 000 megawatts a year of new power generation capacity; lay 22 000 megawatts of cross-border transmission lines; complete the intraregional fibre-optic backbone network and continental submarine cable loop; provide all-season road access to Africa's agricultural land; double Africa's irrigated area; raise household electrification rates by 10 pps; and connect capitals, ports, and border crossings. To this end, the mobilisation of investable funds is critical.